In the beginning, Tim mattered for many reasons, not the least of which was his position as the first born of my generation within my family and that of my wife’s. As such, the hope and optimism that embraced us all, as Tim came into the world, was infectious.

When a new life first appears, it is always a time of joy not only for parents, but for everyone they touch. In this circumstance, friends and family celebrate together with gatherings and phone calls and letters from distant loved ones. Such events are universally celebrated, and as I considered this book, I wondered what story I would tell.

When a new life first appears, it is always a time of joy not only for parents, but for everyone they touch. In this circumstance, friends and family celebrate together with gatherings and phone calls and letters from distant loved ones. Such events are universally celebrated, and as I considered this book, I wondered what story I would tell.

There is nothing unique about the advent of a child. The joy, happiness, and excitement is universally present in every culture. What, then, is special here at the place I find myself, trying to tell his story?

The conclusion I drew surprised me, for it was a cliché. And that is that everyone is unique. One of the many non-universal elements of my son’s story were the many unique facets of his initial circumstance—the circumstance of his birth and existence.

They drove a sense that he was something special. The truth is, though, he is special only to us. My family; his friends; the people who love me; the people he touched. Only we knew him and, as such, were the only ones who could deem him special. In the acknowledgement of his own unique circumstance, though, I hope to underscore the truth that each of us is special and deserving of celebration.

As with my sense of the person Tim is and was, all of us should be celebrated for who we are in the context of those we love, those who love us in return, and the lives we touch.

In Tim’s case, it was as though this first life of a new generation was a harbinger of rebirth. Someone who called out to us through the mere force of his existence that a regeneration had begun. More than just the act of bringing a new life into the world, we all had the sense that a dying family was itself being reborn.

Unlike my wife and her family, my heritage is largely unknown. My parents’ roots were in a rural community just outside of Tulsa, Oklahoma, a place inhabited by proud people who held the social status of peasants. In my youth I had a handful of aunts and uncles, and even fewer cousins in addition to my four grandparents—all of whom were born and remained in and around Tulsa.

My recollection of these people, their homes, and even their surroundings were iconic, symbolic of the age and disrepair that seemed to characterize the lives of most of my Tulsa kin.

“Not a tree nor a house broke the broad sweep of flat country that reached to the edge of the sky in all directions. The sun had baked the plowed land into a gray mass, with little cracks running through it. Even the grass was not green, for the sun had burned the tops of the long blades until they were the same gray color to be seen everywhere. Once the house had been painted, but the sun blistered the paint and the rains washed it away, and now the house was as dull and gray as everything else.”

This descriptive excerpt of rural Kansas from The Wonderful Wizard of Oz is very much how I recall my infrequent visits to extended family. Of course there was color, yet my memories lie to me and yield only the greyscale of decay and age.

My recollection comprised dry fields of dead grass, blistering paint, rusty, abandoned oilfield equipment, and cemeteries with graves of past individuals I was told were my forebears. Everywhere I looked at every place I visited, yielded nothing but the evidence of the dead and dying. And the living, it seemed, I hardly knew at all.

My father, desperate to escape what was for him the rural prison of a small unknown town, joined the Army. He then married my mother, a native of the same area, a year later after having known her only ten days. The Army brought him to Washington D.C. and later he moved my family to a Maryland suburb as he attempted to cobble together an education and make his way in the world.

This was the life my father embraced as he attempted to divorce his rural identity. As I grew older, there would be what seemed dutiful trips to my parents’ past, and always there was a sense that these were not really my people. That they were part of some aging past with no relevance to my present.

When I would ask about my heritage I was offered only speculation. There were tales of small-time ranchers, horse traders, and Native Americans of tribes I’d never heard of. My entire life I have been envious of those who knew their roots as I wondered about my own.

Compounding that reality was the sense that only my father could carry on the family name. He had two sisters, no brothers, and none of his paternal uncles had children. The birth of my son gave everyone a hopeful sense that the family name would continue. For without a boy, the name would die with me and my brothers—a sentiment that settled within everyone and that went completely unacknowledged.

As I wrote that last passage, it gave me pause, as though I were uttering some politically incorrect edict that only male children have value and, of course, nothing could be further from the truth. Truth being what it is, though, the symbolism in the moment of Tim’s birth was quite remarkable.

In our culture, as in most others, the family name continues to be passed down through the father, and my son represented a kind of regeneration for a family ever diminishing in numbers. That a transplanted root was taking hold.

It is not at all lost on me nor should it surprise anyone that my father moved to a metropolitan environment to escape his rural roots, only to transplant his family to rural Texas. Some things, it seems, are inescapable despite our best efforts.

And in the outlying gateway to West Texas, what we couldn’t know at the time was the truth of the symbolism. Like my father, Tim would eventually be the only viable option for passing on the family name in the traditional sense. My biological siblings, who carried the name, had girls. There was no one else from whom the name could be passed. Only Tim.

Thus, the matter of Tim in the beginning was that he was ours. The symbolism of renewal beamed through and swamped the frigid greeting Mother Nature offered. The cold and darkness were warmed and lighted by the greeting our family offered. And like any other family with a first newborn we began the journey of raising the next generation.

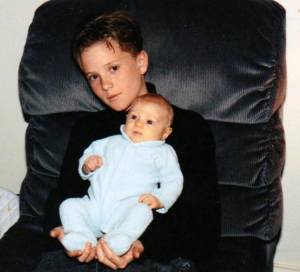

Tim, was well suited for his role as first born. He came into this world with an innate love for children and as the oldest, he cared for, held, and even fed his younger siblings and cousins. There would be so many; 17 of that generation in all.

As he grew and as others were added, it was Tim who showed a genuine sense of nurturing to the newcomers. Just as he mattered to us as our first experience of having and raising children, he began to matter to those who came after him.

He taught them games. He taught them songs. He read to them. He was the one who could be counted on to watch over them and care for them. To me, it was so rare to see a young boy put so much effort into caring for the little ones around him. And as he did, it fostered the nurturing proclivity that came to him so naturally.

This concern for others and putting their needs before his own became his way of being—his approach to the world. And as he grew I repeated to him, over and over “Remember that your obligation, more than anything else, is to leave the world better than you found it.” And I could see in his ever expressive eyes how that exhortation resonated with him so much more than with my daughters when I would say it to them.

He would return my gaze and smile. And in those moments a connection was formed and strengthened between us through the understanding of a simple concept: that we are all part of something bigger and more important than ourselves.

That we are here to serve others both collectively and individually, and that service comes in many forms. Service begins with learning and then with teaching. Begin by understanding how to do for yourself and then to do for others. What it means to care for yourself and then to care for others. To ultimately learn to protect yourself so that you can protect others.

More than anything else, though, Tim learned the value of physical and verbal affection. A sensitive child, he deftly learned to channel that sensitivity into a nurturing and considerate focus on first his siblings, then his cousins, and then his friends. All of this from the confluence of the gift of nurturing with the gentle exhortation of externalizing that gift.

As the child grew from newborn to toddler to adolescent, he embraced a sense that because he mattered, everyone else around him mattered as well. He never saw himself as greater than or above anyone. He saw everyone as an equal, never shunning others, rather embracing them as companions.

Tim was that little boy who innately knew what many of us take years to learn. He knew that, ultimately, everybody matters…