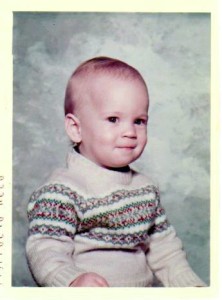

So much time and so many events have passed since those moments when my son, as a child, spoke to me, taught me, and reminded me of the important things. The decades have blurred the memories, which have become malleable thoughts that suit me, now, some 30 years later.

The challenge of writing the story of a life you knew well is the fact that at some point it ceases to be a factual continuum. The story devolves into a series of points, some of which refuse to obey the very chronology of time itself. We remember a thing decades after it happened and we can’t quite place it properly on the timeline next to the other spotty memories. We can’t be certain whether the thing came before or after our next memory as we have since organized it in our minds.

The challenge of writing the story of a life you knew well is the fact that at some point it ceases to be a factual continuum. The story devolves into a series of points, some of which refuse to obey the very chronology of time itself. We remember a thing decades after it happened and we can’t quite place it properly on the timeline next to the other spotty memories. We can’t be certain whether the thing came before or after our next memory as we have since organized it in our minds.

As I began to write this book, one vexing thought overrode all others; it taunts me even now as I try to draw this chapter of my son’s life to a close. The problem, you see, is that I wasn’t taking notes.

Today, it seems, we live life behind the watchful lens of a smart phone, dutifully recording the lives of friends and family as events unfold. The events are compressed and time-stamped and stored like so many books in the libraries of our minds. We display them on social media outlets and share them with others who weren’t able to live it in the moment as it happened.

In this, endeavor, as I struggle to make sense of my son’s life and explain it to you, I regret not having access to that technology. The regret gives me pause, however. In the regret, I find myself wondering what might I have missed if I spent my time recording these moments rather than being forced to experience them.

I recall a moment when he and I walked on the beach of Lake Travis, just the two of us. As is typical, I cannot recall the occasion, the time of day, or the circumstance—only that we were there together. He was about eleven and we still had some time left.

I like to imagine that it was early one Saturday morning, and work seemed far away, perhaps after a MacDonald’s drive-through breakfast. We never spoke, as I recall. We simply enjoyed the sand seeping between our toes, the water lapping at our feet, and the bright Texas sun reflecting off the water.

He mentioned fishing—but there was no time to purchase fishing gear that morning. I didn’t plan for this outing. In a rare moment of spontaneity, we simply went.

And we walked.

Rather, I walked. He danced. He was so happy just to spend time with me and to be in the outdoors on the bank of a man-made lake in the Hill Country of Central Texas.

And he danced, singing some song I can’t recall while running forward into the water and then retreating again. Back and forth, like a puppy discovering free water for the first time.

The images I recall clearly, but every other detail escapes me. I failed to record the details of the event to satisfy my mind at a later time—but the image of the event is forever written on my heart. And that was the character of this event.

It was a moment between father and son that could never be replicated; it was never to be repeated in exactly that way. There would be other moments, good and bad, but this moment, just like all the other temporal points on the timeline of Tim’s life, was unique and separate.

And what is the point, I ask myself. Why write of this moment? Why include it in this story?

The answer, quite simply, is because of what’s missing. The dearth of clarity and detail in this memory says so much more to me about this chapter in my walk with Tim than any recording I might have viewed in an attempt to recall it. Life cannot be experienced through an AVI file, or a GIF, or a JPG.

A timestamp. Regurgitated dialog. The reason for the outing. All of these things cry out for a voice as I try to recall a simple moment I spent with my child—but in the end they matter not one whit. What matters is nothing more than the walk with my son as he danced. He danced, and I walked, and in so doing, we danced together.

He was still at a station in which he had the luxury of dancing through life. He had not yet reached a moment where it was time to walk with purpose. My retrospective view speaks to me and says “Such things were premature.” It was not a time to be an adult. It was a time to be a child. And what technology can capture such a thing—being a child, or any other human experience for that matter?

How can we know by reviewing an event, captured through the lens of a device, our human experience in that moment? The question is, of course, rhetorical. The device tells the mind the sequence of events, but the heart tells the soul the meaning of the experience.

Would I suggest to you that recording such events is folly? No. Rather, I would remind you that time is fleeting. It never stops, it does not tire, and it will not wait. It will instead demand that you immerse yourself in the moment and with all the humility I can muster, I exhort you to heed the demand.

For as I watched the little boy dance along the bank of Lake Travis, I witnessed the heart of a child.

A child born to lower middle-class parents, who would know difficulty most of his life, but one who would also eventually overcome life’s adversity.