I’ve been told countless times since I began this project that I’ve taken on too much ownership of my son’s behavior and the eventual outcome of his life. That I somehow needlessly continue to blame myself for his life’s conclusion and the missteps along his way. I’ve been told over and over to lay this burden down.

In all earnestness I am compelled to offer that this is the certain wisdom of friends and family from the outside looking in, and the wisdom is not lost on me. It is not merely well meaning; rather, it is well-founded. Advice that should be heeded.

In all earnestness I am compelled to offer that this is the certain wisdom of friends and family from the outside looking in, and the wisdom is not lost on me. It is not merely well meaning; rather, it is well-founded. Advice that should be heeded.

The end having been realized, would’ves, could’ves, and should’ves no longer matter. The end is the same and no afterthought can change it. However, as an insider looking out I ask in equal earnest how do I lay down such a thing?

I am merely my son’s father and, as such, I have no way of accurately understanding my role—my shortcomings—which might have led all of us to this place that, perhaps, was inevitable. I am told I am not to blame, but who is competent to judge such things? I have no God’s-eye view to guide me through this valley. I know only that, in any circumstance, we all participate in this trek called life, this journey with no map.

It is statistically rare that a child turns to addiction and rarer still that the child, having succumbed to the addiction, overcomes it and then loses his life a moment later in a circumstance seemingly unrelated to it. At every turn in the writing of this book, I’ve heard from many friends and acquaintances who have lost children to health complications, accidents, and addiction. Within this context a single theme resounds:

If only…

Yet fate is no respecter of intention. We shun the notion of fate because clinging to the notion of control affords comfort, and, indeed, much of the outcome for ourselves is under our control. As a parent I unwittingly extended that concept to the lives of my children as I raised them. I attempted to control outcomes for their lives because I cared for them and wanted only the very best for them—or at least what I thought was best.

In so doing I bought the lie. I somehow thought I could make choices for my children that would serve them well and through the example of my own choices teach them the value of good choosing. What I didn’t count on was independence. The independence forged through rebellion and demanded by growth and maturation.

Most of the time the rebellion is throttled by a sense of self preservation. It is nearly always the case that as the child grows he frequently pushes away from the parent, but insecurity and the need for safety draws him back. Once in a very great while, though, something goes terribly wrong.

Once in a while the child opens the wrong door and steps inside a forbidden room. In the case of addiction, the room is tended by the Sirens who offer fruit that imparts a knowledge only addicts possess. At the moment the knowledge is imparted, his innocence is shattered and he is forever altered, never to return to the safety of childhood.

When an addict says, “…but you don’t understand.” I urge you to heed his comment; it is one of the few times he is telling the truth. Unless you are a recovering addict, you don’t understand. You can only imagine, and your imagination can lead you astray—away from the truth, which is prerequisite to healing.

And if the healing never materializes, parents often second guess themselves with “If only…” The ellipsis of that statement can be replaced with anything your mind can conjure. More discipline. More love. Less indulgence. Less time with friends you suspect were a bad influence. Somewhere inside you, though, you know. You know the outcome was the one your child ultimately chose and that you had very little say in the matter.

I have confessed to my adult children on more than one occasion my greatest lament as a parent:

“I wish I had spanked less and hugged more.”

In those moments I would offer it as though it were some recompense for the parental incompetency I often retrospectively perceive as I periodically recount their childhood. Their response was always something that approximated

“You did your best. You and mom always told us to do our very best and we always tried. We saw that you tried too.”

On this matter my mind and my heart are at war. My mind tells me I did my best but my heart sees failure and blame—and I believe the conflict is inevitable, because it springs from love.

We love our children with a love like no other. We ache when they hurt, we are prone to anger when they are mistreated, and we are joyous when they’re happy—and nobody teaches us this. We are programmed to love them in a way that, we ourselves, do not understand. And when we lose them to some other force whether addiction, estrangement, or death, we’re conflicted.

“You know, when your kid is born, it can still be perfect. You haven´t made any mistakes yet. And then they grow up to be like… like me.”

– Gil Buckman

Parenthood

Perfect. This is what we expect when we bring a child into the world. We see the beautiful fingers and toes, the sparkling eyes, we hear the coos of unspoken love from their tiny lips, and we smell that wonderful infant smell. It’s perfect, and we think it will always be perfect—but it never is.

We make mistakes, and our children pay for them, and what they can’t know is that we pay for them too. We beat ourselves up for all the things we think we did wrong and all the things we wish we had done and didn’t. Most of us, the overwhelming majority, have the luxury of being able to see all the good things our children eventually become. Parents of an addict don’t always have that luxury. Our children don’t always come out OK on the other side.

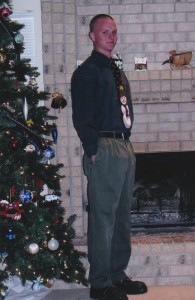

I count myself as one of the fortunate few who witnessed my child struggle with addiction and come out on the other side a better man. In the midst of all the what ifs and the if onlys, for the redemption I witnessed in my son, I am eternally grateful.

…