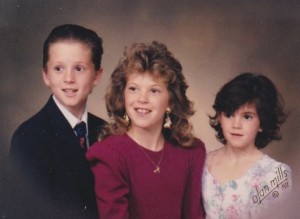

It now occurs to me that, in all of these words so far, as I try to tell my son’s story, I’ve mentioned precious few words regarding my other two children. I was once counseled in the aftermath of Tim’s accident not to forget about my two children who remain.

Regarding the loss of a child, a seductive elixir asserts itself in which the focus tends to be on the one who left and to disregard the ones who remain. The pain of that loss can blind us to many things. The day-to-day difficulties our friends continue to experience. Things at work that require our attention. The needs of our spouses. But the most important potential casualty is that of children left behind who experience their own brand of grief.

Regarding the loss of a child, a seductive elixir asserts itself in which the focus tends to be on the one who left and to disregard the ones who remain. The pain of that loss can blind us to many things. The day-to-day difficulties our friends continue to experience. Things at work that require our attention. The needs of our spouses. But the most important potential casualty is that of children left behind who experience their own brand of grief.

We love each child equally, but it’s so easy to become baptized in the pain of the lost child that we forget the child standing right in front of us. If you’re not careful, a role reversal can occur in which remaining children worry for the welfare of their parents and in so doing may ignore their own pain. That shift can feel a lot like diminished love to the child left behind, but typically not until much later when they are no longer caught up in the ensuing chaos.

I tried so hard to shield my daughters, Rachel and Ashley, from my pain because I wanted to be a good father to them and not allow my pain to burden them. Then a strange thing happened.

It was the day of Tim’s funeral, a single week after his passing. There was no body to bury, no convincing visual cue that he was once here and then was gone. Tim lost his life in a burning pile of twisted metal wrapped around a tree. Cremation was our only real option, and as a result there was nothing at the service to announce “Here lies your son.”

We had photos, but the mind is a complicated thing and such a situation causes you to doubt everything you think you know. Nothing is spared the skepticism, including both his existence and demise. A photograph of you standing next to a smiling young man with your arm around him cannot convince you that the moment ever occurred. Likewise, in a dichotomous twist, the absence of a recognizable body gives rise to questions that feed the denial of his passing.

I watched as, Rachel, threw herself headlong into the funeral plans. When people think of a death in the family very little attention is paid to the social burden and logistics of trying to plan for such an event. While dealing with the loss of a sibling, she put together a 20 minute photo montage set to music and drafted a eulogy, both of which she presented with aplomb. This, as I sat in my office watching life go by alternating between complete detachment and burning grief.

Had it been my call, there would have been no funeral at all, but everyone else needed this, and so I put on my best face and steeled myself for the social event of which I wanted no part whatsoever. Afterward, my wife insisted that we make an appearance at my parents’ home where there was food and family. I objected to both but she insisted. She also insisted that I eat and I objected to that as well.

Predictably, my body rejected the food in a rather humiliating episode outside my parents’ home and I found myself sitting in the passenger seat of my wife’s car, violently weeping. Then I looked up and saw my two daughters standing next to the car peering through the window.

“Are you OK daddy?”

“I just want my baby back.” was all I could muster.

“I know, daddy. Momma said the same thing. You don’t have to come in, but are you sure you want to sit here alone?”

“I’ll be fine. I’m sorry I made a scene.”

“You know, grandpa won’t be around forever. He’s 80, and you know the things you’re thinking about with Tim? You don’t want to feel that way with your dad. You should call your parents more.”

And through all of this I found humility. My two daughters—my youngest children mind you—were suddenly thrust into a role I swore I would not allow. But in such circumstances grief becomes a clever thief who steals your control of circumstance.

In that moment I was forced to look at these two people I brought into the world and see them as adults. No longer could I see them as little girls, one of whom I rocked on my forearm to console her colic and the other who was satisfied to sit on my lap for hours at a time.

These women, siblings of the very son the loss of whom I was mourning in that moment, slipped into the role of parent, and and as I looked at them I suddenly recalled that Tim cared for them in exactly that way as well.

In a recent conversation with Ashley, she related an anecdote that bears repeating in the context of the quiet period when things were still intact. According to her, when my wife and I were not around, he would tell them dark, frightening tales in an attempt to create adventure for the three of them. In so doing, he would bravely lead them through the danger, safely to the other side.

Knowing this is a cherished clarification for me. He loved these two girls, his sisters, and tried very hard during this time to make sure they felt protected and loved, even if his demonstrative methods were childlike.

That was a big part of who he was.

In story after story regarding Tim, after his departure a common theme surfaced: that of caregiver to the weaker among him. In the stories Ashly told, he was fabricating situations to create drama. But I believe the drama had an intention that was ultimately noble.

Children learn and mature through imagination—and Tim’s imagination was vast and vivid, to say the least. Somehow, he intuitively understood the benefit of exercising that imagination, and brought it to bear as only a caregiver could. In the process, intentionally, I think, he created a bonding experience not otherwise possible. A platform for a lifelong bond with so many people—not just his sisters—that was nearly unbreakable.

This is a primary element of his legacy. No. It is his legacy.

In our culture we reserve the notion of a legacy for someone to whom we assign greatness. We contemplate the legacy of Presidents, scientists, inventors, medical doctors, and explorers. FDR and Reagan, Einstein and Curie, DeBakey, and Lewis and Clark. These notable historical figures all have an enduring and well known legacy. Each of us, though, have our own legacy, merely lesser known.

We each have been shaped by what we have taken from and given to this life and those who have lived it with us, and for that reason we assign the greatest legacy of that based on what we give to others. Gandhi, Mother Theresa, St. Francis of Assisi, Jesus. These are historical examples whom we hold in the highest esteem because of the example they offered us.

I hope my legacy is that I touched someone and made a difference in his or her life, and I believe you do—in fact—have a life altering legacy. I’m certain you have touched someone’s life because your life matters and I like to think you wouldn’t waste that opportunity.

Likewise, I do not accept the notion that my son was defined by his addictions and the behavior they drove any more than I should be defined by the last harsh word I spoke or the last critical thought that foisted itself on me.

Tim’s life mattered but, more important, your life matters because he has left, and you remain. And that notion begs the question: What will you do with the time you are given here on this plain of existence?

On a number of occasions I told all three of my children,

The only thing you own in this life is your time. Spend it well…