I’ve devoted more copy than I care to admit to the notion of spending time. Every moment now seems so precious, and I am continually reminded by my inner voice that it’s family who deserves that currency, whether biological or adopted.

I’ve devoted more copy than I care to admit to the notion of spending time. Every moment now seems so precious, and I am continually reminded by my inner voice that it’s family who deserves that currency, whether biological or adopted.

As such, I was spending that time with my daughters by way of phone calls one evening. During the conversation with my youngest daughter, Ashley, I spontaneously extended an invitation.

“Just calling to check in. How are you?”

“Fine.”

“How’s William?”

“He’s fine; swamped as usual.”

“The kids?”

“Also doing really well.”

“You know, I’ll be with my friends at Third Base tomorrow. You’re welcome to join us.”

“That would be nice.”

“OK; meet us. I’d love to see you and the kids.”

“See you there.”

The next day sitting on a patio with Fran and Jeff, two friends of more than 20 years, I watched as my daughter approached from the gated entrance holding her oldest, Julius. I stood and strode over to greet them.

“My little man, Big J!” I exclaimed as I kissed her forehead and gently swept the two year-old from her arms to mine.

He smiled.

I took my seat and he quietly sat on my lap looking at the other two men at the table, smiling. I kissed his cheek and instinctively inhaled. He still had that infant smell I remember from holding little ones thirty years prior.

I had forgotten.

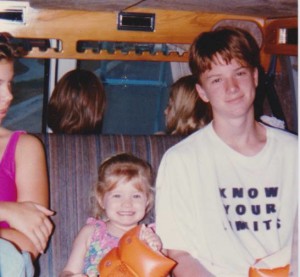

Through the powerful catalyst of olfactory memory I was transported to a moment before the quiet period. I remembered Tim; the same sandy blond hair, brown eyes, long eyelashes, and gentle smile; a child who lived so long ago, whom this child will never know.

This is one of so many things I forgot as each of my children grew and transitioned into adulthood. The physical sense I was able to perceive as I held each of them. It’s more than the things you remember.

It’s more than what you see from across the room when you come home from work. More than the chatter of attempted conversation from a toddler. More than the nagging sense of dread of first days at primary school and the worry of whether your child is fitting in. More than the nagging question of whether you’re raising a well-adjusted child or a maladapted ne’er-do-well.

It’s the essence you sense of that child as he sits on your lap and smiles.

And in that moment, as my grandson sat on my lap, quietly taking in the world around him, I remembered how, during the quiet period, Tim would watch. He would see the younger children and would be content to spend time with each of them, intuitively sensing their individual needs and deftly meeting those of each.

And somewhere beneath that seemingly tranquil surface, a caldron boiled, mostly unperceived by the rest of us. Retrospectively, I believe we, the adults, should have had a sense that this child needed something; something we were not giving to him. An endeavor that reeks of failure.

As children, we wait with an unending anticipation of becoming adults, a craving for independence and a drive for accomplishment. Then we become adults, and it seems we spend much of our time fearing failure, and trying so hard to get everything right—especially with our children, and in the process questioning our every action. Finally, when our children are grown we wonder, “Did I fail her? Did I give him everything he needed? Did I miss something?”

Rarely do we rest with our current station, enjoying the moment, living in it as I believe we are meant to.

As I sat there with this child, two friends, and my daughter, I realized that Tim knew, during the quiet period, what I have tried to come to terms with since his passing. He understood how to live in the moment, to enjoy simply sitting or playing and just being, especially in the company of others.

He understood what it meant to take this moment and just to live it.

I am not beguiled by any grand notion that I fully understand my son, nor what was truly in his heart at that time, nor even whether his ability to live in the moment is somehow different than any other child. If I am honest with myself, I must admit that the last few passages are romantic ideals I cling to as I try to make sense of the senseless.

It makes no sense that a parent should outlive his child and as humans we are driven to piece together a story to help us understand a situation that should never be. But there is value in the piecing of it together.

When I therefore imagined on that day with my grandson that Tim had a habit of living in the moment, I can learn the value of his example as I recall and perceived it.

Here’s the wonderful thing that I hope to give to you: you don’t have to lose a child to learn this lesson. As you sit here reading these words, you are no doubt among people who love you and are in your life because of the beauty you bring to each of them.

The message of this book is so simple. It’s a message that is too often said, yet too rarely heeded.

Be present with those who love you and immerse yourself in the love they offer, but more important, love them in return. For it’s the loving that offers the greatest reward.