“Dad,

Thank you for your last letters and including excerpts from your blog. I honestly laughed till it hurt, at least for a moment. The way you described Rachel and Ashley’s weddings was eye opening. I never really thought of finding humor in a wedding; they always seem so somber.

And then it hit me, just how much I’m missing in this place. I’m so angry with myself. First my sisters’ weddings and now Rachel’s first pregnancy. It seems I’m missing all the important moments…”

The important moments. So many. Our first day of high school, first date, first kiss, the first time we make love, the birth of a child, your son’s college graduation, your daughter’s wedding day, the birth of a grandchild.

Most of us take these moments for granted when we think of them in the future tense, expecting that we will see them, experience them, live them. All the while, completely unaware of the fragile nature of our very existence and by extension our future. That our world, our plans, and our lives are ultimately subject to something far more powerful than ourselves.

We have the illusion of control as we traverse the continuum of our lives and that of each person we encounter. We think we can plan tomorrow—when in point of fact we have no guarantee that tomorrow will even come.

By and large we do not even consider the possibility that in the next moment a marriage can end, a prison door can be slammed in our face, or a life can be lost. Most outcomes are the result of our own actions, and most of us plan our lives around a hopeful future. But occasionally the fray of life besets our hopes and derails our dreams. And when life demands the toll of the fray we are left bewildered.

For so long after my son’s passing I wondered over and over “What is the point?” “Why do we bother living at all when something as precious as a life you love can be taken so easily, so callously.” “What is the point of this thing we call life?”

This sort of thinking is the result of the madness of grief brought on by the loss of someone who was not supposed to die. Someone who was not infirm. Someone who had so much left to do. Someone who’s mind and body was healthy, young, and vibrant.

In many ways this is the experience of the prisoner. “I had a life.” they say. “There was a place for me in the world.” they lament. “I was part of something now lost to me.” they opine. It is a sort of living death in the sense that you are deprived of the things that make you who you are.

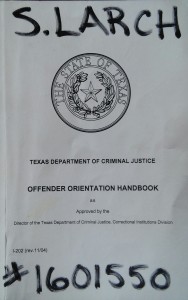

In the Texas justice system, it is more than your liberty that is taken from you; you are stripped of your independence, your family, your very identity. Upon entering the prison system you are issued something called the

Offender Orientation Handbook

Across the top of the top of the book is written the name by which you will be known for the duration of your time in the institution of penance.

And across the bottom is written the number that identifies you as a ward of the state.

During his incarceration he was no longer Timothy Evans Oliver, first born son of Guy and Dawn Oliver, he was thereafter known only as S. Larch #1601550.

“…I feel like I’ve lost more than just time or freedom. I’ve lost being a part of something greater than myself; the ambitions and plans I made for my future. I feel like my family is finding itself—coming into its own.

I have been removed from all I have ever known and am left with only memories and the things I’m told are happening outside these walls. The family that I now realize meant everything to me is moving forward without me and I hate it with everything in me…”

“What is the point?” “Why bother living at all when something as precious as my family, my future, my very identity can be taken from me so easily, so callously.” “What is the point of this thing called life?”

The very questions I myself posed in the aftermath of my son’s departure from this world he must surely have asked himself upon his departure from his home, his family, and society. But in the asking we abandon the seductive suggestion of forfeiting this thing called life. We instead begin to seek answers in earnest.

The questions themselves indicate a spark of life that stubbornly refuses to be extinguished. It is only when we stop asking such questions that hope is truly lost. The questions that assert themselves when seemingly everything—or at least that which is most precious to us—has been taken from us, is the human spirit demanding to be reborn and to find a way. And in the end, the questions propel us forward.

“…There have been so many things I didn’t anticipate in prison, not the least of which is the terrible weight of cruelty in the hindsight I’ve gained—but there are other things that feed my optimism as I try to move forward.

Some of the other inmates have befriended me, and we have a saying that we use to lift each other up:

‘It’s a minor setback for a major comeback.’

Although the setback doesn’t feel so minor at times, it keeps me and all of us going and looking forward rather than backward…”

And in this exhortation I found hope. My son, was able to somehow muster a sense of optimism in the face of privation, loneliness, and regret. Having experienced the valley of despair he saw the mountain and slowly, patiently made his way toward it, not knowing how long the journey would be or exactly where it would take him.

In those dark hours following his accident I saw the example he was trying so hard to offer to his fellow inmates and to me.

When our children are born we love them unconditionally; we need no reason to love them. We are programmed from the outset to feel an attachment to them—a bond with them. But as time passes and we watch them grow into adulthood, we are confronted with a battery of reasons, having nothing to do with the fact that they are part of us, to love them.

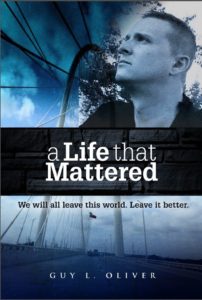

In my hour of darkness, among the many other beacons that lit my path, was my son. I saw the light he tried to give others. I saw the redemption I had longed and waited for. I saw the man who would go about the business of mankind, touch the lives of others, and leave the world better than he found it…